PROSE AND CONS 1993

As its text this hand-made limited edition book uses an excerpt from “Mr. Entertainment’s Diary,” which chronicles my gradual recognition and eventual embrace of my entertainment-culture imprinting. (See The Velvet Grind.)

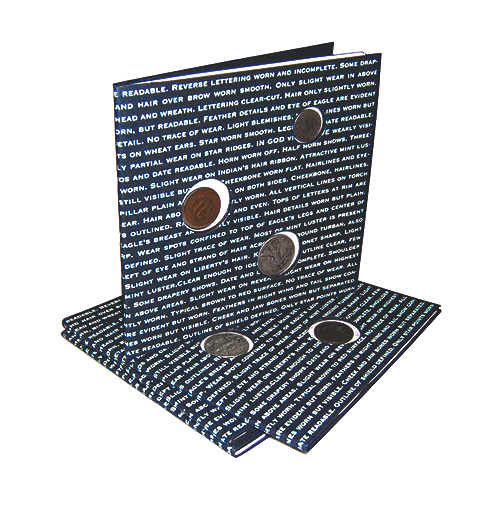

Incorporated into the cover design of each of the eighteen books is a unique trio of antique coins. One copy in the edition includes the actual coins that figure in the story (reprinted here in its entirety); the other seventeen books include a substitute coin set — i.e. fakes. Buyers of the book are not informed whether their coins are genuine or a substitution.

Incorporated into the cover design of each of the eighteen books is a unique trio of antique coins. One copy in the edition includes the actual coins that figure in the story (reprinted here in its entirety); the other seventeen books include a substitute coin set — i.e. fakes. Buyers of the book are not informed whether their coins are genuine or a substitution.

April 16th As Entertainmentman, I seem to have acquired the ability to inhabit or disinhabit, at will, the commitment to a personal content. I can stand outside of it, and watch it fold, or I can re-inflate the idea of personal content and slip it on like a perfectly tailored second skin. For the past few weeks I’ve thought of this newfound ability only as a kind of personal problem — that is, while it’s fascinated me, I’ve felt guilty about both ability and fascination. This morning, however, an innocent spring morning, an incident occurred which provides exactly the intellectual ammunition needed to cover my flight from older, unicontextual configurations of sincerity.

Walking along Houston Street at the northern edge of Soho, I was stopped by a young man who seemed not only down and out but, as indicated by the slow, stumbling manner of his request for assistance, enjoying an afternoon on some drug or another. As I prepared to deliver the automatic refusal favored in New York by the league of self-important young men on the go, the bum asserted that he didn’t want money. Swaying on the sidewalk, he slurred and growled that he wanted only to have a phone call made for him. He showed me an envelope with the name “Dr. Stone” and a seven-digit phone number written on it. Inside the envelope were three coins. Each coin looked both old and foreign, and each was presented in the manner of the amateur numismatist, pinched between two pieces of clear cellophane and displayed in the circular window that had been cut into two pieces of white cardboard, the entire sandwich neatly stapled together at the edges. A brief description of each coin, its date, and its market value — all three in the thousands of dollars — was written in a neat, legible hand on the white cardboard.

The young man asked me to dial the number written on the envelope, and to inform Dr. Stone that three coins, presumably his and presumably lost, had been found. Though I was in a hurry to get on with my day, it seemed a simple enough favor to perform, so I popped a quarter into the pay phone, dialed the number, and when a woman’s voice answered, asked for Dr. Stone. In a moment a gravelly voice identifying itself as that of Dr. Stone came on the line, and I carried out my duty, informing the doctor that three apparently rare coins had been found in an envelope bearing his name. “You found them!” Dr. Stone shouted. “Where did you find them? This is fantastic!”. I explained that they’d been found by another young man who appeared in desperate need of a windfall. Dr. Stone said that there was a cash reward of $1000 for the safe return of the coins, and that whoever had found them had only to return them to to his home at 877 Park Avenue in order to claim it. Holding my hand over the phone’s mouthpiece, I related to the young man the news of his good luck, whereupon, to my surprise, the guy groaned that if he couldn’t even dial a phone number to reach the doctor he could hardly get up to 877 Park Avenue. While the doctor waited on the line, the young man told me that he didn’t care enough about the reward to go all the way uptown to retrieve it (perhaps $1000 was enough money to force him to change his life and he had no interest in tempting the possibility), and proposed that in exchange for $75 I could take the coins and claim the reward himself. After hesitating a bit, as I had a luncheon date and errands to run, I agreed, as it seemed foolish not to seize the opportunity which had fallen into my lap. I told Dr. Stone to expect me with the coins later that afternoon. The doctor said that anytime that afternoon would be fine, he would be at home all day. I promised to call before coming uptown, signed off, and hung up the receiver.

The young man asked me to dial the number written on the envelope, and to inform Dr. Stone that three coins, presumably his and presumably lost, had been found. Though I was in a hurry to get on with my day, it seemed a simple enough favor to perform, so I popped a quarter into the pay phone, dialed the number, and when a woman’s voice answered, asked for Dr. Stone. In a moment a gravelly voice identifying itself as that of Dr. Stone came on the line, and I carried out my duty, informing the doctor that three apparently rare coins had been found in an envelope bearing his name. “You found them!” Dr. Stone shouted. “Where did you find them? This is fantastic!”. I explained that they’d been found by another young man who appeared in desperate need of a windfall. Dr. Stone said that there was a cash reward of $1000 for the safe return of the coins, and that whoever had found them had only to return them to to his home at 877 Park Avenue in order to claim it. Holding my hand over the phone’s mouthpiece, I related to the young man the news of his good luck, whereupon, to my surprise, the guy groaned that if he couldn’t even dial a phone number to reach the doctor he could hardly get up to 877 Park Avenue. While the doctor waited on the line, the young man told me that he didn’t care enough about the reward to go all the way uptown to retrieve it (perhaps $1000 was enough money to force him to change his life and he had no interest in tempting the possibility), and proposed that in exchange for $75 I could take the coins and claim the reward himself. After hesitating a bit, as I had a luncheon date and errands to run, I agreed, as it seemed foolish not to seize the opportunity which had fallen into my lap. I told Dr. Stone to expect me with the coins later that afternoon. The doctor said that anytime that afternoon would be fine, he would be at home all day. I promised to call before coming uptown, signed off, and hung up the receiver.

The walk to the bank was a short one, and on the way my new partner and I made awkward conversation. I learned the young man’s name, then listened to Joe’s history. How he’d been thrown out of the house by his parents at thirteen, lived in foster homes, run away and made the street his home. When we reached the bank, I withdrew from the cash machine the money I’d promised him. Thanking me, Joe handed me the envelope with the coins, and we said goodbye. I wished Joe good luck and watched him shuffle off towards Bleecker Street.

The walk to the bank was a short one, and on the way my new partner and I made awkward conversation. I learned the young man’s name, then listened to Joe’s history. How he’d been thrown out of the house by his parents at thirteen, lived in foster homes, run away and made the street his home. When we reached the bank, I withdrew from the cash machine the money I’d promised him. Thanking me, Joe handed me the envelope with the coins, and we said goodbye. I wished Joe good luck and watched him shuffle off towards Bleecker Street.

After lunch, I made a call to Dr. Stone to say that I was on my way, but there was no answer. I used the time to take care of errands, then returned home, where again dialed Dr. Stone’s number. Still no answer. Pulled out the phone book and looked up “Stone”, checking for doctors. No Dr. Stone listed on Park Avenue, either as a residence or as an office. Checked the medical listings, which confirmed that there was no Dr. Stone on Park Avenue. Knowing that certain apartment buildings are listed in the Manhattan White Pages, I looked up 877 Park Avenue. No listing for 877, but there was one for 879 Park Avenue, so dialed the number. A voice answered, and after I’d ascertained that I was speaking to the doorman, I inquired about the location of 877 Park Avenue. The doorman to 879 Park Avenue stated that there was no 877 Park Avenue.

I’d been conned.

This afternoon, I felt by turns stupid, embarrassed, and angry, until, early in the evening, I realized that “Joe” and “Dr. Stone” had conned one of the few people who could actually benefit from obtaining the objects used in the con. As a result of their ploy, three objects charged with a rare and unique valence of ambiguity had blundered into the zone of art, a context in which hard evidence of intention is always useful, sought, and celebrated. The fact that these coins have a shadowy anecdotal history gives them an eerie potential for presentation in public life that they could have acquired in no other way. (The victim of con artists, I now have the opportunity to produce genuine Con Art. Ironically, if I can manage to guide these professionally insincere coins into the art context in just the right way, I’ll be able to re-sell them for considerably more than the amount of the offered reward.) Even if it had occurred to me to do so, were I to have walked into a numismatist’s and purchased three coins in order to assign to them the story of the con, those coins could not have had the same twisted integrity, because they would have possessed an altogether different history. They would have been mere souvenirs of a groundless fiction. Instead, I have on my hands something stranger than fiction: the embodiment of a stubbornly authentic inauthenticity.

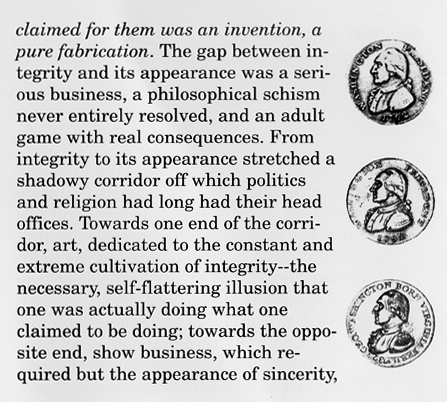

But the value of this experience is not that it’s provided me with the material for Con Art; however amusing, it’d be a one-time only project. It’s much more interesting to consider what the coins represent: specifically, the gap between integrity and the appearance of integrity. As an idea, this gap possesses its own integrity. What is the difference between integrity and its appearance? What are the signs by which a difference can be discerned? Indeed, can one even tell the difference? These are powerful and alluring questions, in sophistication worlds away from the minor aesthetical distinction between “real and fake”. These coins are real coins. What was claimed for them was an invention, a pure fabrication. The gap between integrity and its appearance is a serious business, a philosophical schism never entirely resolved, and an adult game with real consequences. From integrity to its appearance stretches a shadowy corridor, off which politics and religion have long had their head offices. Towards one end of the corridor, art, dedicated to the constant and extreme cultivation of integrity — the necessary, self-flattering illusion that one is actually doing what one claims to be doing; towards the opposite end, show business, requiring but the appearance of sincerity, and then only in the presence of an audience, yet entirely believable when unleashed….

But the value of this experience is not that it’s provided me with the material for Con Art; however amusing, it’d be a one-time only project. It’s much more interesting to consider what the coins represent: specifically, the gap between integrity and the appearance of integrity. As an idea, this gap possesses its own integrity. What is the difference between integrity and its appearance? What are the signs by which a difference can be discerned? Indeed, can one even tell the difference? These are powerful and alluring questions, in sophistication worlds away from the minor aesthetical distinction between “real and fake”. These coins are real coins. What was claimed for them was an invention, a pure fabrication. The gap between integrity and its appearance is a serious business, a philosophical schism never entirely resolved, and an adult game with real consequences. From integrity to its appearance stretches a shadowy corridor, off which politics and religion have long had their head offices. Towards one end of the corridor, art, dedicated to the constant and extreme cultivation of integrity — the necessary, self-flattering illusion that one is actually doing what one claims to be doing; towards the opposite end, show business, requiring but the appearance of sincerity, and then only in the presence of an audience, yet entirely believable when unleashed….

July 18th For some time now, have kept the little gap between integrity and its appearance under observation, turning it over in my mind and studying it the way one studies a snapshot that has caught some disturbing trick of the light. Curiously, nourished by my observation, the sliver of space has grown, little by little, until at last, today, I’ve discovered that it’s expanded into a philosophy. Yesterday the gap had been inside me, today I’m inside the gap. There’s room enough to move about freely.

July 18th For some time now, have kept the little gap between integrity and its appearance under observation, turning it over in my mind and studying it the way one studies a snapshot that has caught some disturbing trick of the light. Curiously, nourished by my observation, the sliver of space has grown, little by little, until at last, today, I’ve discovered that it’s expanded into a philosophy. Yesterday the gap had been inside me, today I’m inside the gap. There’s room enough to move about freely.