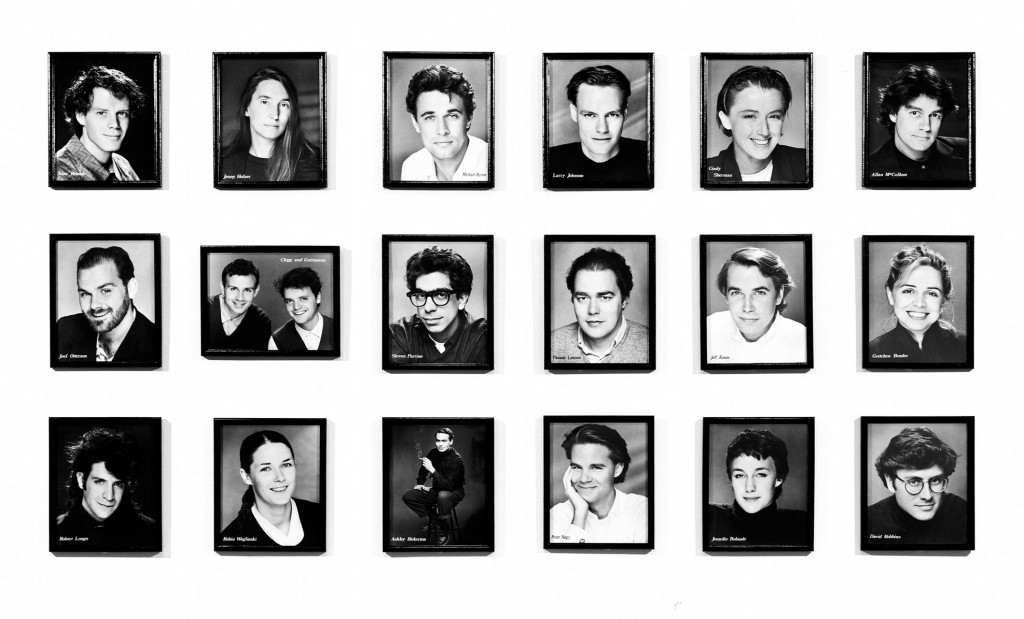

TALENT 1986

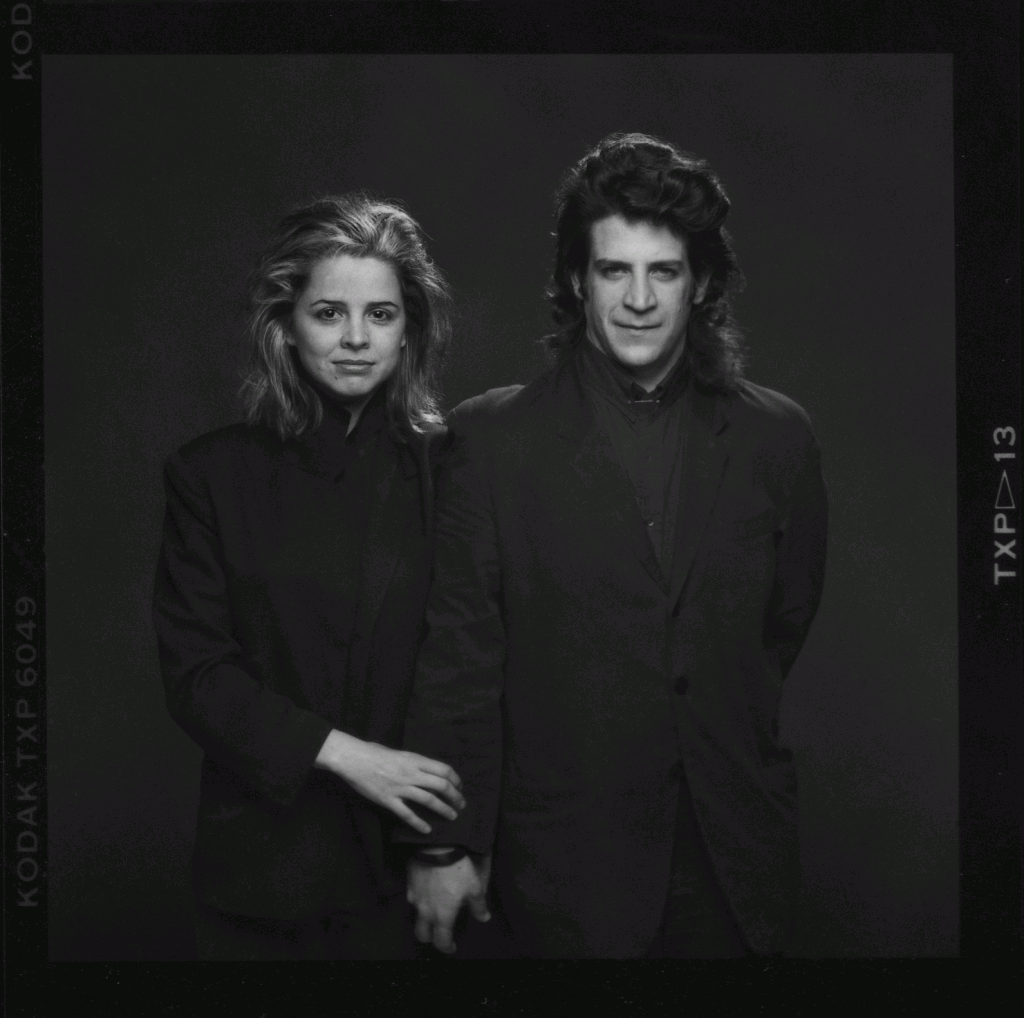

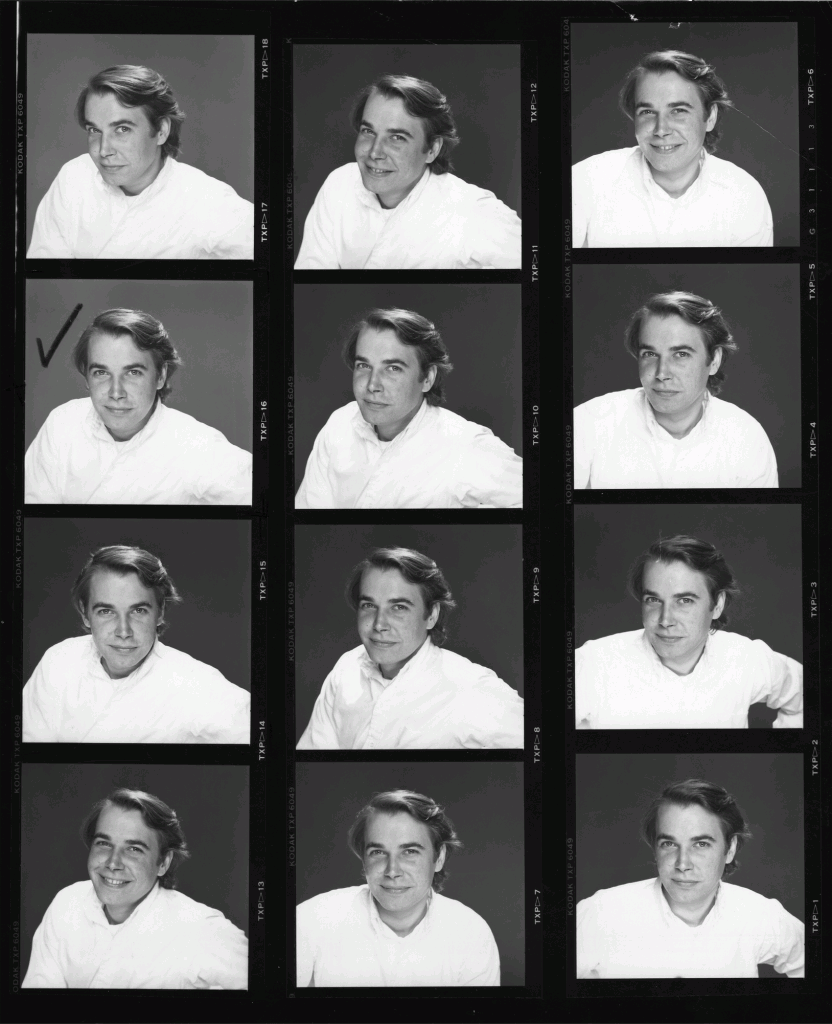

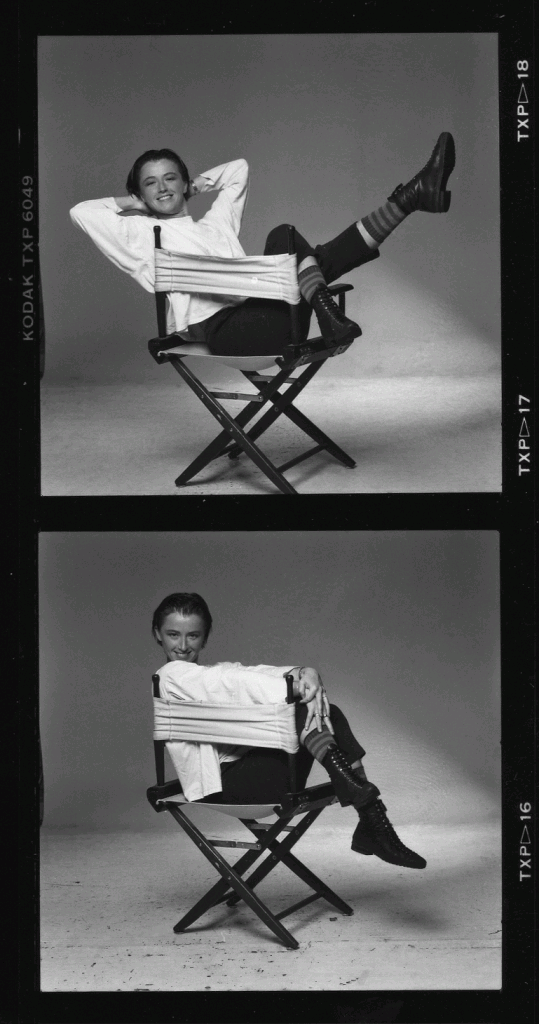

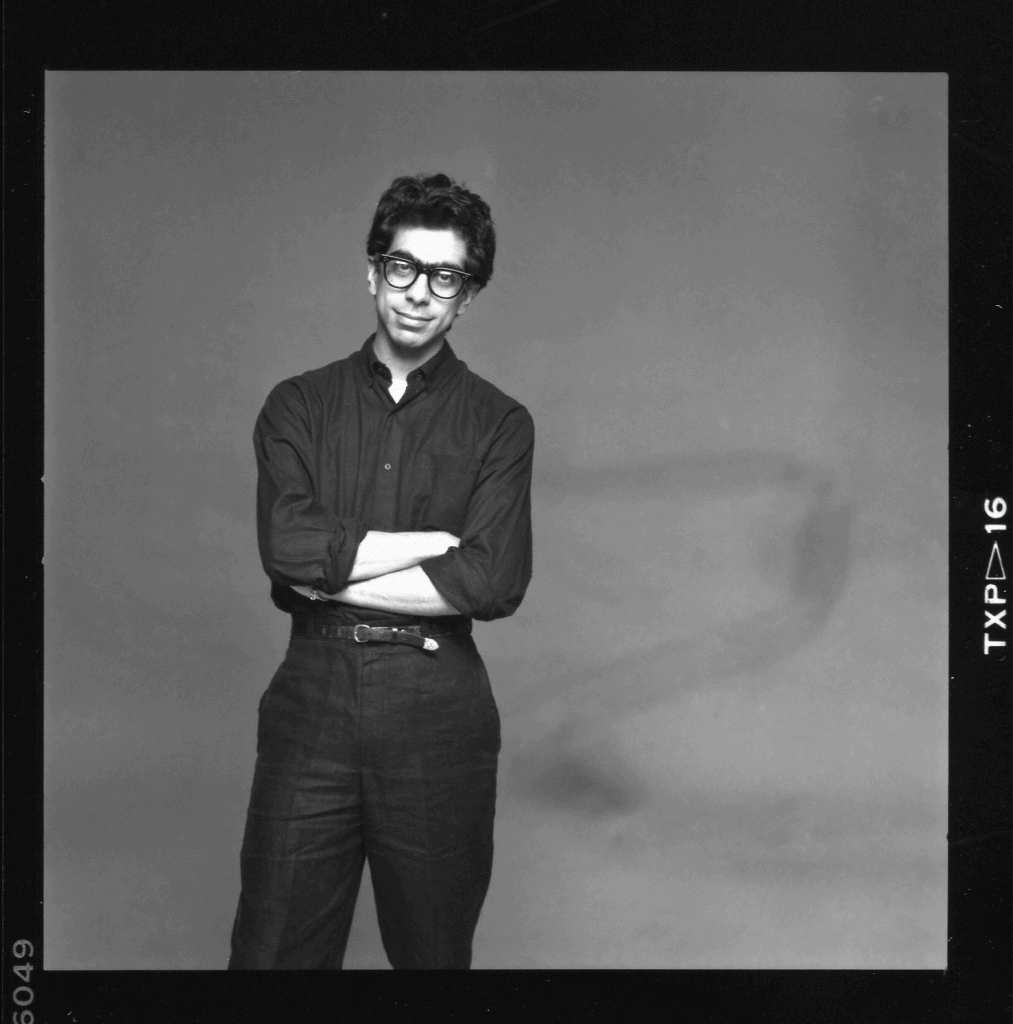

Eighteen silver gelatin prints, each 8″ x 10″. Top from left: Alan Belcher, Jenny Holzer, Michael Byron, Larry Johnson, Cindy Sherman, Allan McCollum Middle: Joel Otterson, Clegg & Guttmann, Steven Parrino, Thomas Lawson, Jeff Koons, Gretchen Bender Bottom: Robert Longo, Robin Weglinski, Ashley Bickerton, Peter Nagy, Jennifer Bolande, DR

Eighteen silver gelatin prints, each 8″ x 10″. Top from left: Alan Belcher, Jenny Holzer, Michael Byron, Larry Johnson, Cindy Sherman, Allan McCollum Middle: Joel Otterson, Clegg & Guttmann, Steven Parrino, Thomas Lawson, Jeff Koons, Gretchen Bender Bottom: Robert Longo, Robin Weglinski, Ashley Bickerton, Peter Nagy, Jennifer Bolande, DR

Write When You Get Work: Susan Morgan interviews David Robbins on his installation Talent

Susan Morgan: The title that you’ve chosen, Talent, has quite a number of connotations. There’s the dismissive way that “talented” is used to describe artists, indicating remarkable facility and a serious lack of ideas. Or the way that film crews refer to the actors as “the talent,” a description that has nothing to do with any measure of skillfulness but is simply the name for the group of people who appear in front of the camera.

David Robbins: I chose the word talent as a particularly non-committal word. I think we generally perceive talent as something positive, but its meaning is somewhat shapeless, malleable. “Talent” is a sort of pre-contextual word meaning goodness, but you can’t avoid contexts.

Artists today operate in two contexts simultaneously: on the one hand, they operate as people involved with difficult intellectual, political, and moral stances, and on the other hand, they are public figures who function as entertainers. I wanted to make a picture of this entertainment context that artists share with one another regardless of which medium they use or which context they represent — the context of a specific public life. To do this I had to take the point of view of the audience.

There were a number of other objectives. I wanted to engage an objective means of picturing, a picturing system other than art’s; I wanted to picture artists as the larger business culture pictures them; I wanted to make a picture of artists that was consistent with my own experience of the art world. And I was interested in doing portraits. I’d always liked Man Ray’s portraits of artists, that clean black and white look, but I wanted to inject more contemporary content into it. The “talent headshot” satisfies all these conditions, and there is the added bonus that headshots have their economic life — the way they function in the economy as photographs — built directly into them.

To do all this, it was very important that these pictures be headshots, not just look like them. I didn’t want them to be parody, but to be fact. So rather than make them myself, I hired a photographer who does entertainment photography for a living. I think that artists have become a species of entertainment, particularly in the ’80s when artists have become media stars. Personally, I’ve always thought of an artist’s style as his “act,” the idea of working up a style is like working up an act; and then dealers and curators book your act into their venues.

There’s also a social side to it. In New York during the last twenty years, the kind of art officially approved by the downtown critical mafia has been leftist, deconstructive work that complains about capitalist culture. But a lot of these deconstructive artists have been very successful within capitalist culture, they’ve become financial aristocrats as well as sensibility aristocrats. It seems there is a certain hypocrisy there, and it bothers me. I mean these hard-hitting-critique objects end up being bought by the same corporations and collectors that buy totally reactionary art; so I think a lot of the self-flattery among artists and the art world about the social effectiveness of art proves illusory. It’s not the end of the world, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves about our power. And at the same time, Talent is meant as a critique of the business culture which does this to artists. The nation that makes its artists into entertainers by denying complex content is in trouble; it censors the important political potential contained in creative thought. And when this happens, the culture slowly suffocates, generation by generation. So considering all this, I made Talent to frame this double-edged condition.

But don’t artists find being described as entertainers trivializing and offensive?

Obviously I can’t speak for all artists, but some do find that the idea of being considered entertainers rankles, in part because they like to report on the culture but not to be reported on. But don’t understand me: the idea of the artist being an entertainer is something that I also want to stand for. I think that it is the current reality, in part. And anyway entertainment is an enormous idea: it includes the idea of pleasure, of bringing pleasure to people, it includes a complex body of assumptions about what brings pleasure, it includes a critique of labor because it provides relief from labor, it includes ideas about audience, and about how all these things are structured within a particular culture. The United States, for example, is an entertainment culture, not an art culture; so to deal with entertainment is to deal more directly with the realities of American life. Entertainment includes the idea that pleasure cannot itself be hierarchized; its symbols may be hierarchized — champagne versus beer, for example — but pleasure itself as a human experience may not. And this is a radical cultural idea, radically egalitarian. To me these are much more satisfying issues to be working with than, say, ideas about art materials, media, or procedures. There are all sorts of assumptions about art — that it’s good, that it’s useful — but we have no real proof of that. I’m interested in an externalized view of art. I’m interested in the ways that people outside art perceive how art and artists function. I want to explore the role of the artist rather than the role of art.

How did you present this project to the artists involved? I know that some people turned you down.

I told each artist that I wanted to make a picture of them, that it was a respectful picture, it wasn’t going to make fun of them. There were a few artists who turned me down, some for reasons they didn’t explain, some because they misunderstood the project as promoting the image of the artist, whereas Talent addresses the problems which are created by promoting the image of the artist.

One of the interesting things about this project was that basically I was relying on the trust other artists had in me. I couldn’t do it without the sense of community. That’s an important part of this — that artists would believe enough in my position to subject themselves to being interpreted in this way. From the outset the work had a shared content; it wasn’t limited to my viewpoint. Also, that the artists believed enough in my integrity and the idea of the piece to allow literally a hundred of each of these images to be released into the world. All artists are familiar with how difficult it is to control an image once the image has been released into life. And here, they were allowing for far less control than usual. I was going to be doing things with the images in terms of publication, each of the artists was given a set of the images, so they would probably be doing things with them and the people who bought the pictures would have ideas about what their public life might be…so the artists really trusted me and that content is embedded in the work.

How did you present the project to the photographer?

I engaged James Kriegsmann Jr. to take these photographs. The Kriegsmann studio has been located in the same building off Times Square since the ’40s; the space now occupied by the photography studio used to be a nightclub. It was called Zimmerman’s Hungarian Supper Club. It’s a wonderful place with diamond-patterned mirrors and chandeliers. There’s a great sweeping marble staircase leading down to the studio, and the downstairs bar is still there. The Kriegsmann family and employees eat lunch sitting at red leather banquettes. Evidently Zimmerman’s was a very popular place in the ’30s and they’ve kept that wonderful supper club atmosphere. James Kriegsmann Sr. established the studio and he’s photographed everyone, from Frank Sinatra to The Supremes in their early days. Kriegsmann Sr. no longer does the photographs but his sons carry on the business. James Jr. took all the pictures, thirty-six shots for each artist, and I selected the final image.

For this project, I was functioning as agent for all the artists. I booked the shootings and paid the bills, made sure the artists got there. At first I didn’t tell the photographer what I was up to, but he asked me what was going on since no agent had ever booked eighteen people before.

Were you not afraid that if the photographer knew these people were artists he would attempt to make arty portraits? Make everyone wear berets?

I didn’t want the question to arise. I wanted the artists treated like anybody else. I wanted to keep it as authentic an experience as possible for the artists. I told them to dress in black, grey or white and to be clean, to look as if this were the real thing and they were going to use these photos to get work. I mean, if the art world were structured slightly differently, artists would actually send these things out with their slides.

What about the retouching of the photographs? There are no dark circles under anyone’s eyes, everyone is terribly bright-eyed. Is the hopeful world one where no one grows tired?

Well, it’s a caricature of optimism. Everyone is presented as a cheerful, inviting looking person. I wanted to make the viewer more aware of the anxiety of being an artist by totally excluding anxiety. Some sneaked in — Jenny Holzer looks rather wary in her picture, and I think Allan McCollum looks frankly anxious. He looks a little like he’s caught in the headlights. I was afraid of showing the photograph to him, and when I did I said, “I like it because you look like a fearful, handsome man.” And he said that’s what he was, so it was accurate.

Another sub-theme of this work was deciding who to include. I became a curator. That curatorial thing of inclusion/exclusion is one of my anxieties: you know, who are you going to allow into history? In Talent you are aware of who is not included. The fact that everyone is white, for example. That whiteness weakens the effectiveness of contemporary art. It’s a problem that’s totally ignored. [This situation has improved dramatically since the year the interview was conducted.]

I started out wanting to picture people who acknowledge the role of entertainment in their own work — Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, Alan Belcher, Gretchen Bender; they were using entertainment language in their work — “film stills,” “spectacle,” advertising and television photographs. But then I realized that, to the business culture, it doesn’t really matter or make any difference. I decided on a wider variety of artists because the business culture positions all artist in the same way, as the same species, without regard for subtle distinctions of media or meaning. So the curatorial question broke free of its initial sociological bent. I had to decide what other criteria to use for selecting artists, because I wanted to make it seem more like a portrait of a generation. The criteria became increasingly personal. It took four months to complete the project, so I was really living in it. I didn’t want to pretend that it was a portrait of the art world, but rather of my art world, of people I knew and really liked or those I admired and wanted to meet — people who made my experience of the art world really pleasurable. It’s not a portrait of a movement but instead a personalized portrait. One of the things I like about this is that it reveals the subjectivity of authority, which a lot of my work is concerned with.

So it is your subjectivity as author that personalized the group portrait, rather than the usual attributes assigned to the “artistic individual.”

The artist as presented by the mass media is an exhausted, stale image inherited from the nineteenth century: someone half mad or mad with genius, starving, unreasonable, romantic, impossibly poetic. This image of the artist seemed to be completely the opposite of my experience in the art world. By and large, the artists I know are very cheerful, funny, generous, reasonable people. And I resented the sort of image that was presented of them — of us — as mad, romantic dreamers hopelessly out of touch with reality. In fact our reality is at least the equal of the dominant model of reality. So I wanted to present a new picture more in keeping with my experience, which is that these are good people, and that art is an entirely reasonable activity in the world.

The pictures convey a very upbeat image.

Yes, upbeat and unapologetic. They are consistent with the look of headshots, which tends to be upbeat. Headshots are pictures made for people trying to get work so they present themselves as reasonably friendly types, easy to work with. The pictures are optimistic, forward-looking images of artists who hope to get more work, who are looking forward to the future, who have futures. “Hope to be working with you soon!”

Do you see the photographs as acting to dispel the myth that artists are hermetic, precious people who do not want to participate in the world?

Sure. These are pictures of people who want to participate in the culture and not be isolated and ghetto-ized and made powerless. Artists generally are moving towards greater participation in the wider world. There are all sorts of good mid-western American homilies about “doing the best you can” and “just wanting to take part.” That idea of participation is extremely important. It has to do with insisting absolutely on your right to participate in and construct the culture, whether you are educated in culture or not. It’s an anti-elitist, anti-jargon approach. You don’t need permission to participate in culture.

Originally published in Artscribe International, September/October 1987

◆◆◆

Talent at 25

Had I never lived in Hell’s Kitchen, the tattered neighborhood bordering Times Square, my most well-known artwork, Talent, would not exist. Proximity to the legendary hub of American entertainment, in 1986 gritty and vulgar compared to today’s family-and-corporation-friendly fun-zone, afforded daily contact with the grammars and representational strategies of show business. To any such as I who had a fascination with entertainment culture, Times Square was an archeological motherlode. Traversing it I came away lightly coated with twentieth-century show biz silt.

In those days I was just a year or two into inventing a public life as a visual artist, making and exhibiting pictures and objects. But I’d come to art-making late, in my mid-twenties, and already I had inklings that art was to be only a veneer on a deeper, formative imprinting which derived from prolonged exposure to entertainment culture — the birthright of American children born after the Second World War. How to map my role as an “artist” onto this entertainment imprinting? How to wrestle this imprinting into form? Much of the contemporary art that I saw displayed in the galleries struck me as brittle re-arrangements of prior discoveries about art, and only half-heartedly present-tense. Rejecting their sentimentality (even my choice of neighborhood signaled it: I didn’t dwell downtown, where the visual artists clustered), I intuited that cultural coordinates more authentic to one with my — make that our — imprinting were to be mapped, somehow, on the relations between contexts rather than within the value system of any one context. I didn’t know precisely how to go about doing this but, as any artist must, I began by being honest about my aims.

Metro Pictures, then located in Soho, was the first gallery to exhibit the finished work, in a group show. In those days Metro was the gallery that focused most consistently on the complex relationship between media culture and visual art, so displaying the headshots in that context made sense. Even in that congenial setting Talent looked extreme, however. Whereas the Metro Pictures artists treated entertainment as subject matter, still keeping it at arm’s length, Talent collapsed that distance. The effect was to more nearly equate artists and entertainers. Many viewers found this news unsettling. “Too au courant for its own good,” Roberta Smith adjudged Talent in the New York Times. (New York remains resistant. Talent is included in numerous public collections and museums in the U.S. and Europe but, as of this writing, no New York museum has acquired it.)

As their subsequent, extensive exhibition history attests, though, these photographs had got something right. In the twenty-five years since its debut Talent has entered dozens of collections. So frequently has it been exhibited and reproduced, in fact, some curators and critics doubtless categorize its author as a one-hit wonder. Although I was confident that in Talent I was conveying (however satirically) a basic truth about the location of artists in our business civilization, I do admit to being surprised that this work has penetrated so deeply. To what has its appeal been due? How do its collectors, which now number more than ninety, perceive it? As eighteen portraits of (mostly) famous artists? As trophy heads? (One noted collector would acquire the piece only if I autographed it, celebrity-style, thereby making his set, snore, “special.”) Artworks exist to be interpreted, and “misinterpretations” are inevitable. Often the piece is mistakenly referred to as Fame — not even remotely the work’s subject. From museums where Talent is on display I still get occasional reports of visitors wondering aloud whether these photographs are “some kind of joke.” Talent has been known to rile art world insiders just as much. I recall being condemned by a Cologne-based cell of institutional critique artists who read Talent’s cool demotion of artists as complicit with the Reaganite era of its creation. They overlooked that Talent can be interpreted as institutional critique that holds up a mirror to artists themselves.

Well, no matter: As every artist knows, the thing done matters far more than anything which is said about it. Talent fixed an unsentimental portrait of art’s contemporary location within our business civilization, and a present-tense image of the artist, and that has stood.

How accurate is Talent’s portrayal? Has the (arguably cynical) cultural formulation therein crystallized — the equation of artist and entertainer — really come into being? Do we see artists promoting their exhibitions on late-night TV talk shows, flogging their latest wares in the manner of actors and pop musicians? Have artists become blips on the tabloid culture’s radar? Are they paid to endorse luxury cars and wristwatches? No. But when has the future ever been a simple extrapolation of present-day conditions? If any aspect of Talent’s prognostication has come true we should expect it to be far more complex, subtle, and specific to this time than would be the mere realization of some stale ‘80s fantasy about seeing Cindy Sherman guest on Late Night with David Letterman.

Surprisingly, my own career trajectory, post-Talent, has pointed in a very different direction from these developments. I did not continue to focus on entertainment subject matter — hadn’t I already addressed it? — and indeed opted out of the version of the art world Talent described. I did not join the ranks of the art stars. The resume of the successful artist — typified by continuous production, representation by a constellation of top galleries, name recognition, absorption into the “right” collections, occasional museum survey shows, coffee-table picture books, and steadily rising auction prices — isn’t mine, and for better or worse that has been my own doing. The same instinct that came up with the idea for Talent directed me in years subsequent to feel my way toward a different model. Taking Talent’s content to heart, I traded the fantasy of being an Important Artist for what was, to my personal taste, more interesting work: exploring the grey zone between art and entertainment, which work was “more interesting,” in my view, because more expressly of this time. In a sense, taking Talent as seriously as I did derailed my art career. At a time when I should have been capitalizing on the acceptance my art had won and ramping up its production, I instead evolved away from those rituals of production and display which define the theater of the art context. Over the years I abandoned, by stages, the art object, the exhibition format, even all gallery affiliations, in order to discover what shape my imagination might take were I not continually programming it to produce in “art” formats, as the annual exhibition schedule of the successful contemporary artist dictates. I pulled the plug, cleared my schedule, “retired.” Instead of thinking always in terms of objects and exhibitions, I gradually developed skills that led to writing books and creating videos (television, even) — both of them favorite formats of the pop mother-tongue and thus endowed with a capacity to travel through our culture (and our economy) in very different ways than does art. Two of my books — Concrete Comedy (a history of twentieth-century comedy read in terms of actions and objects) and High Entertainment (an argument for applying art’s experimentation to entertainment formats) — pointedly espoused “alternatives to art.” To reinforce the distinction I meant to represent, I began referring to myself as an “independent imagination” rather than an “artist.”

My idea of the “independent imagination” is born from the phenomenon of a digital revolution that enables anyone who has access to a computer, camera, and microphone to create efficiently using the pop media — TV, film, music — whose distribution had been controlled heretofore by corporations. With revolutionary potential playing out both in the unprecedented ease of production of works that employ the grammar of mass communication and, equally, their distribution, today’s creative imagination explores an exhilarating degree of real, practical independence. Digital technologies have liberated us from reliance on the production systems and economies of the entertainment industry at the same time that digital distribution, via the Internet, enables us to bypass the evaluative system of the art context. Able now to say what we want to say in the way that we want to say it and to deliver the result to an audience, directly and unfiltered, we are freed to develop cultural positions and forge personal paths that disregard two long-dominant over-determined cultural systems. In their place we create and distribute advanced pop-media work, of varied intention, using new, still-forming systems. These new production and distribution opportunities, since they do not merely permit but actively implement, and thus encourage, experimentation, are already influencing what’s being made — how it is structured, what it looks and feels like, and what it has to say. Additionally, the relative ease of digital production today bestows a level of personal creative control over pop-media technologies previously known only in painting, sculpture, and other fine art practices. Today a painting and a television show may be created with roughly equivalent outlays of effort.

So successfully, to my mind, does the concept of the independent imagination hurdle the late twentieth-century cultural tensions expressed in Talent that were I thirty years younger I would enter public life today as an independent imagination, set up operations within the emergent digital High Entertainment culture, and from there volley with the future. Read against this backdrop of wishfulness, the irony that it is none other than the art context that has consistently sponsored my trajectory away from it becomes all the sweeter. Like a parent packing a lunch for a petulant child bent on running away from home, it is the world of artists, galleries, and museums, not Random House or HBO, that values and underwrites the line of inquiry I’ve pursued. I don’t kid myself that it is otherwise. Wiser and more worldly than I, elements of the art context foresaw that however unsentimental about art my experiments may be, I still wind up an artist of a kind, and I’m grateful they did. Expanding my production vocabulary — what might be made, where it could go, how it could get to an audience — liberated me from the constraints of “thinking through art” and the corresponding model of the artist that’s promoted by the art system, and for me that was necessary work. But today, having secured the freedom of movement my imagination required, I’m able to value anew and without irony the specificity of art’s methods and aims.

This essay originally appeared in the book accompanying the exhibition “Talent at 25″ presented at Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, May 2012.